On April 15, I presented a webinar about Audacity, the voice recording and editing program I've been using since my days in journalism school. (...)

Read moreAre You Interested in Diversifying Your Client Portfolio With Voice Over Work?

Do you have a pleasant voice and good pronunciation? Have you ever translated something that was meant to be read aloud? Why not think about becoming a voice over artist?! (...)

Read moreWhat Do Freelancers Do When They Get Sick?

What do freelancers do when they get sick? Here are some thoughts on health-related scenarios that could keep you away from your computer and ideas on what you can do (...)

Read moreIs it Possible to Balance Your Biggest Life Project—Your Children—and Working as a Translator?

“Woman, what are you doing in front of the computer already?” or “How come you didn’t answer the email I sent you half an hour ago?" (...)

Read moreBlog Interview

Today I was featured on Patricia Fierro's blog with a four-question interview in Portuguese about my educational background in translation, professional experiences, specialty areas (...)

Read more"Tools and Technology in Translation" to be published in Brazil

Today, a campaign on Bookstart.com.br goes live to gather funds and publish a Portuguese version of "Tools and Technology in Translation" in Brazil. (...)

Read moreTestimonial: Why I am part of UCSD Extension

I started going to UC San Diego Extension Foreign Languages classes in 2004 to become more confident in Spanish, my third language. (...)

Read moreContributing to ATA's Literary Division Publication "Source"

The latest issue of "Source"―a quarterly publication of the American Translator Association's Literary Division (ATA-LD)―features a summary of the literary presentations (...)

Read moreAttract More Clients in the New Year with a Straightforward, Concise Cover Letter

If one of your business resolutions for 2016 includes staying busier by attracting new clients, you may enjoy the tips I'm sharing in this new video. I talk about how to write (...)

Read moreIntroduction to Swordfish: A Cross-Platform CAT Tool

On December 23rd, I presented a webinar about Swordfish, the computer-assisted translation tool I've been using since 2008. This webinar session, "An Introduction to Swordfish (...)

Read moreWhen 3% Felt Like 30: A Roundtable On Literary Translation In The 60s & 70s

During the 38th Annual Conference organized October 28-31, 2015 by the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) in Tucson, Arizona I attended a panel titled “When 3% Felt Like 30: a Roundtable on Literary Translation in the ‘60s and ‘70s,” which was moderated by Steve Bradbury with panelists Stephen Kessler, Andrew Schelling, and Marian Schwartz.

Having started working as translators in the 1960s and 1970s, each one of them reminisced about how they first discovered literature not written in English and how, back in the day, it seemed that there was more translated literature entering the U.S. market than there is today. The title of their panel is a reference to the fact that, in average, 3% of all books published every year in the United States are works in translation, as indicated by Three Percent, a resource for international literature at the University of Rochester.

Steve Bradbury, a translator of Chinese poetry and editor of Full Tilt: A Journal of East-Asian Poetry, Translation, and the Arts, introduced the panel and started out by talking about his own experiences as a teenager in the sixties. “I remember it vividly. It was like I had put my finger in a socket and was electrified,” he recalled finding a shelf of foreign books at a local bookstore.

Spanish-to-English translator and poet Stephen Kessler said he was an A student of Spanish in high school and remembers discovering the works of Federico García Lorca and Pablo Neruda, the main Spanish-languages poets at the time. “You usually needed to go to Spain or Mexico to find material in Spanish,” he said, explaining these titles were hard to come by.

Andrew Schelling, poet and translator from Sanskrit to English, talked about the political context of the era. “Finishing high school in 1970, the main event was the Vietnam War,” he said, mentioning that reading foreign books was a way to resist the U.S. socio-political climate at the time. “That was part of that energy: finding these books, the search for alternative values, foreign literatures.” He said he decided to learn Sanskrit, mentioning the popularity of the “Beatles and bedspreads” counter-culture. “Popular culture kept India alive in our imagination,” he added.

When it was Marian Schwartz’s turn to talk, she said she found her presence in the panel a little contradictory. As a translator of Russian classic and contemporary fiction, history, and biography, she reminded the attendees that the USSR wasn’t very popular back then due to the Cold War with the United States. “If anyone read a Soviet novel, they’d be discredited,” she emphasized, saying that back in the sixties she was learning Russian in Harvard as a dead language. “There weren’t many Westerners going to Russia. Professors were not fluent in Russian because there wasn’t much contact.”

The panel was then asked about how exactly they started out as translators after falling in love with foreign cultures and literature. Stephen said he felt awkward at first when reading poems and comparing Spanish originals and English translations side by side, admitting he was young and impressionable. “I know grammar. I can read. I can speak Spanish when I travel... What’s wrong with me? When I read these poems, I get something completely different!” he recalled. “Everyone was just winging it, so that was how I got into translation: I was looking at the material available then and didn’t think they were that good. I thought I could give it a shot.” He said translating also made him a better poet.

Andrew added that being a translator wasn’t a full-time activity back then and many wondered, “If you want to be a translator, what are you going to do for your day job?” Marian agreed, saying that she was still freelance-editing to pay her bills and couldn’t live on translation work alone.

She told attendees that she started working in the seventies, when students of Soviet culture and literature were discovering the Silver Age of Russian Poetry from the 19th and early 20th centuries. “Established U.S. poets were bringing Russian poets to the American audience through translation,” she recalled.

On the more practical side of things, Marian said publishing houses were more artistic back then. “If someone had an MBA, they’d be laughed at,” she joked. Soon after that, the corporate mentality started to take over and publishers were being bought and merged. “That’s when the number of literary translations dropped,” she contrasted.

She also mentioned the underground feeling of literary translation dissemination at that time, and remembers typing five copies of translated material in onion-skin paper, keeping a copy to herself, and passing the rest on to four friends, so they would do the same and carry on the tradition.

Stephen agreed with the improvised character of translations back in those days. “Our group had a fly-by-night operation. We’d put a circle around a C for copyright. We didn’t even have ISBNs. We just wanted to publish and I was semi-visible for a few seconds.”

The panel discussed the relationship between translators and publishers at more length. “New Directions, by then, was an endorsement of high-quality work,” Steve emphasized. “A third of their titles were translations. And we didn’t care they were translations; we just wanted to read good material. We wanted to read books that would change our lives.”

Marian mentioned New Directions as well. “I didn’t have copyright back then, but they wanted to publish my translations when they took over, and they wanted me to have copyright of my translations.”

When talking about what changed since then and, considering the lack of official numbers, whether they believe that the “electrifying feeling” may give us a false notion that more translations were being produced in the sixties and seventies compared to now, they admitted that they may see the past through rosy goggles.

“We weren’t just reading literary translations; we were reading the same literary translations and talking about it with passion,” Steve chimed in. “There are a lot more translations being published today, but who’s reading them? The real problem for us isn’t to have books published; but having books read,” he added.

“Maybe we think of it as a golden age because we were young,” Stephen admitted. “Back then, the U.S. felt like a broad culture, instead of the specialized culture of nowadays. That’s what we’re nostalgic about it: it was easier to find those books that would change our lives.”

“We also don’t have bookstores as a meeting place anymore, where people discovered things together,” Marian explained. “There’s money out there for something that is potentially exciting,” Steve added, on a positive note, mentioning the digital culture, the popularity of audiobooks, and the “clicking generation.”

Stephen agreed, but didn’t rule out printed literature altogether. “Paper books are becoming LPs. It’s for hipsters,” he suggested. “Something becomes viral for ten minutes. Then something else becomes viral. That’s why people are so stressed out nowadays,” he joked.

RAFA LOMBARDINO is a translator and journalist from Brazil who lives in California. She is the author of "Tools and Technology in Translation ― The Profile of Beginning Language Professionals in the Digital Age," which is based on her UCSD Extension class. Rafa has been working as a translator since 1997 and, in 2011, started to join forces with self-published authors to translate their work into Portuguese and English. She also runs Word Awareness, a small network of professional translators.

Why I Use A CAT Tool To Translate Books

Computer-Assisted Translation―that's what CAT stands for. If you're not in the translation business, or if you're in the book translation business, odds are you're not familiar with it. (...)

Read moreWhat it's like when you lose a client you've been working with for 10 years

This is a longer, unscripted video (I promise this will be an exception!) because I wanted to give you a better perspective of what it's like to lose a client (...)

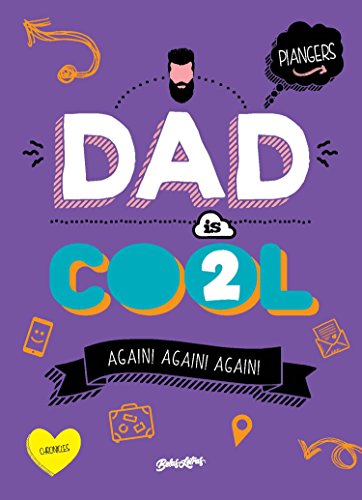

Read more"Dad's Cool" By Marcos Piangers

Correct me if I'm wrong, but the dream of every translator is to work on a book they can translate as if the words were being whispered directly into their ear, effortlessly. A book they could have written themselves, given how familiar they are with the subject. A book about something that is already part of their universe, so much so that they already know what the next line will say

Through the recommendation of a dear friend and diligent translator, Editora Belas Letras contacted me to work on a translation sample of O papai é pop, written by Marcos Piangers, a media and radio personality in Brazil. I hadn't been aware of his work and, to this day, I still haven't met him in person, but after translating his book, I feel as if we sat down at a bar, shared a beer or two over some traditional Brazilian petiscos and talked about raising kids.

He has two daughters, 10 and 3 years old; I have a 7-year-old daughter and a 3-year-old son. He is a hands-on dad who changes diapers, pretends the spoon is an airplane while feeding babies, reads bedtime stories, takes them to adventures at playgrounds and malls, and gets irritated if someone asks him whether he is "the nanny for the day." I have one of those at home―a hands-on dad, that is―and it's a truly moving experience to realize you couldn't have chosen a better person to share this journey called "raising kids." I'm sure that is how Mrs Piangers feels, too.

From the very beginning, while working on the test translation, which involved two of the 32 short stories that compose the book, the words came easily to me. That was the feeling I go throughout the translation of the entire book: Piangers' writing is sincere, it flows naturally. Besides, we're virtually the same age (he is twelve days younger than me) and, having grown up in the ‘80s and ‘90s in Brazil, we both have the same cultural references. Readers feel like they're having a conversation with him, and, indeed, most often the conversations you have with other adults who also have children are about parenting.

However, he's not theoretical about the topic; he doesn't recommend this or that method or technique to make sure you're successful; he knows that failure is part of the deal and that sometimes your children are the ones teaching you something. Piangers is an observer who has picked out true gems from his parenting experiences to write about in a way that makes them universal. And he doesn't talk about the perfect, precious moments only... there's a lot of guilt and poop in this book.

I felt that this universal subject, written in such a conversational tone, deserved a translation faithful to the concepts and images, not just to the words written in the original Portuguese. I can only hope I have done it justice. Whenever my translator brain took over the mommy brain throughout the translation, I looked for inspiration in my real life. "How would I say this if I were talking to a friend about one of my kids?" or "What would my husband say (has said) in this situation?"

For translators or language buffs reading this, here are a few examples of sentences that, translated literally at the word level, could have jarred readers from their spell and thrown them back into stark reality, while my intention was to keep English-speaking readers in the same kind of trance I was, preferably reading through the book without interruptions (while the kids were at school or sleeping.)

Período de adaptação = "Period of adaptation," which became "Period of adjustment"

Pra verem o que é bom pra tosse = "So they see what is good for their cough," which would be completely lost in translation and became "That should teach them a lesson"

comida industrializada = "Industrialized food," which would bring an utterly different image to the reader's mind compared to "processed food," a jargon so dear to new parents who are careful about what they feed their children

enquanto abraçamos nossos filhos no sofá = "while we embrace/hug our children on the sofa," sounds way more forced than "while cuddling with the children on the couch"

Não quero ser saudosista = "I don't want to be nostalgic" could work, but then we'd get into that argument about the true meaning of saudade, that Portuguese word everyone says is untranslatable, and we'd have the Nostalgia Team vs. Longing Feeling Team and nothing would work quite as good as "I'm not into talking about the good old days"

- O fato de a maioria do meu almoço cair na minha roupa = “The fact that most of my lunch fell on my clothes” was translated as “The fact that I’m wearing most of my lunch,” which is a common joke among people who aren’t as careful as they should while eating and end up getting their clothes all dirty during meals

Here's a link to an interview and a TEDx Talk I watched

while trying to get the right tone of Piangers' writing

(This book translation was a true sensory experience!)

At the expense of sounding cheesy, this is an ideal book for parents to read to their children before bed as well. The short stories are brief, yet say so much, and kids will surely identify themselves with the little ones depicted in them. Also, the paperback version looks gorgeous, with all the drawings kids can color, with a special space for them to draw Daddy.

All in all, my goal was not to make anything sound awkward or out of place in the English translation, but to guide readers effortlessly through these short stories. I thought about my American, Canadian, British, and Australian friends I'd like to give a copy of this book to. I thought about how I'd like to have them experience the same thing I felt while reading Pianger's words in Portuguese, the feeling that "I could have written this book, too!"

But could we? Perhaps Piangers’ skill lies in making us imagine we could, even if, in fact, very few of us have the talent to do so and would still have time to raise kids. Because of all those mixed feelings the author aptly describes throughout the book, mommies and daddies are bound to be cheesy and laugh and cry while reading "Dad is Cool."

P.S. I wrote this review while potty training my son, as my daughter walked around the house, tablet in hand, listening to Justin Bieber songs.

RAFA LOMBARDINO is a translator and journalist from Brazil who lives in California. She is the author of "Tools and Technology in Translation ― The Profile of Beginning Language Professionals in the Digital Age," which is based on her UCSD Extension class. Rafa has been working as a translator since 1997 and, in 2011, started to join forces with self-published authors to translate their work into Portuguese and English. She also runs Word Awareness, a small network of professional translators.

Win-Win Project: What If A New Translation Industry Were Possible?

I've just joined a project that promises to help individuals have access to information through translation and make it possible for translators to contribute to a multilingual web while properly charging for their services.

The Win-Win Project is in its developmental stage right now, but it has the potential to become a platform where a group of individuals may get together to order the translation of content that is important to them and pitch in to pay a professional translator. Content creators could also resort to this system to order the translation of their work into multiple languages to better serve their communities.

Watch the video above ―narrated by yours truly― for more information on how the project will work. And, if you also think it's a wonderful idea for all parties involved, make your contribution to the crowdfunding project here.